Architect and researcher Chiara Dorbolò writes in topos 111 about Rome – a city with a violent juxtaposition of different and transient identities.

Billboard

Skyscrapper

Halfpage

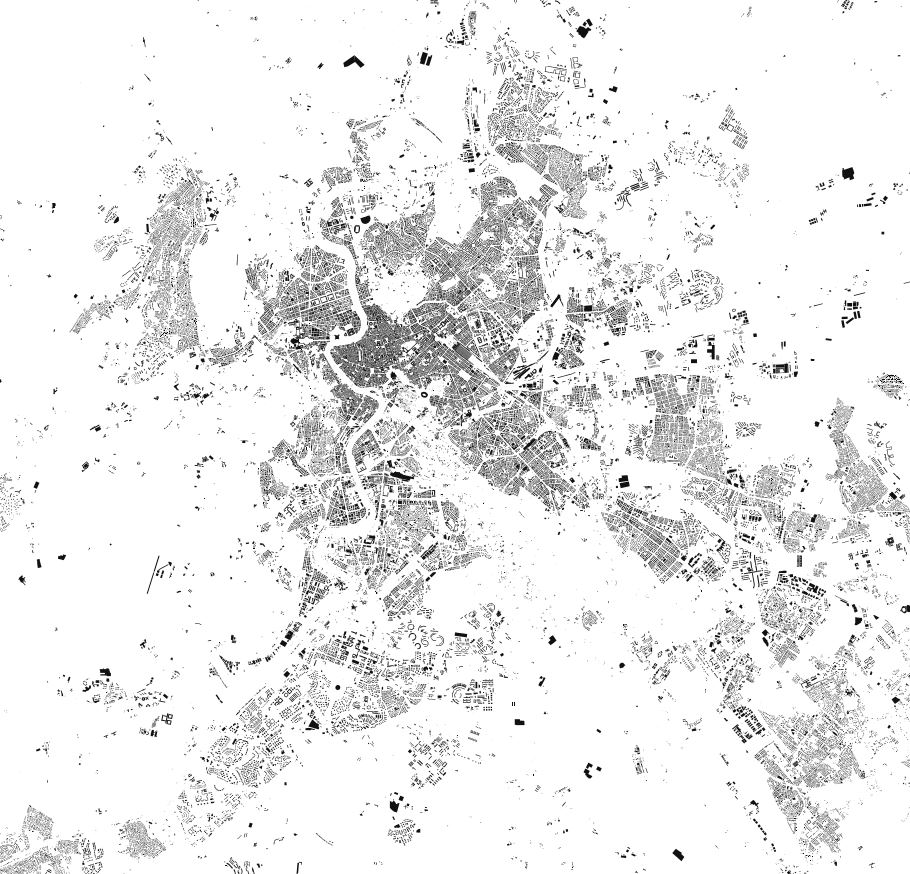

Rome – the eternal city. To architect Chiara Dorbolò the Italian capital is anything but eternal. On the contrary, its unique character is the result of a sometimes violent juxtaposition of different and transient identities: The authoritarian and the rebellious, the formal and the spontaneous, the new and the old, the devoted and the careless. In times of the coronavirus a new identity has arisen and another vanished: The empty and the overcrowded. In a way, the absence of urban life brings Rome back to its promised eternity.

Last weeks’ footage of Rome has a confounding familiarity to it. Its streets emptied by the government response to the pandemic, the eternal city seems to have finally honoured its reputation, suspended in a timeless state devoid of human life. Yet, the photos of the Spanish Steps, one of the city’s most famous tourist attractions, only depict the final stage of a process already started in 2016, when the monumental stairway was cleaned as part of a costly Bulgari-funded operation. After the marble was returned to its original white, some suggested fencing off the area off and locking it overnight to avoid a quick return to old habits and dirt. The proposal was rejected, but then in June 2019 the municipality issued a ban on sitting, eating, or drinking on the Spanish Steps and other monumental stairways. While policemen monitored the steps, whistling at incredulous tourists, Roman intellectuals were divided between those in favour of protecting the monuments and those who considered the ban an overly authoritarian measure. This coming summer the debate will not arise again.

“The city centre has become an open-air museum, where speculation has gradually forced out local residents and activities.”

Until last year Rome was the main tourist destination in a country that relies heavily on tourism for its gross domestic product. In the effort to monetise its historical heritage, the city has faced the same difficulties as other European tourist hotspots such as Barcelona, Amsterdam, and London. The city centre has become an open-air museum, where speculation has gradually forced out local residents and activities. A common example is Campo de’ Fiori, the famous square where the 17th-century philosopher Giordano Bruno was burnt at the stake as a heretic. The only important square in Rome without a church, it was historically associated with the tension between Catholicism and secularism. It was a meeting place for hippies in the ‘60s and feminists in the ‘70s, and later it became very popular among foreign students and professionals (mostly American) in Rome. A couple of decades ago, despite the already numerous tourists, and the chaos often wrought by football fans on weekend nights, the area was still home to a lot of permanent residents. Every morning, they would stroll the market stalls set up at dawn by farmers coming from the city’s outskirts. Now the market is still there, but no one is doing their grocery shopping there. Produce has been mostly replaced by souvenirs, fruit salads to go, and local delicacies. The clochards, artists and activists who used to populate the square have given way to weekend travellers and tourism workers; shops have turned into restaurants and bars, and apartments into short-stay accommodations.

“Have Romans given up on their city centre?”

As the tourist area expands, a similar process is affecting other, not so central neighbourhoods as well. In Monti and Pigneto, for example, local movements are now recognising and strongly opposing gentrification. A notable example is the Ex SNIA, an artificial lake born from a real estate mishap and then reclaimed by the neighbourhood as a public asset. And yet, cases of angered residents fighting speculation in central areas are quite rare. For the most part, opposition to gentrification in the city centre stems from intellectuals who strive to save specific cultural sites rather than social movements opposing a broad urban phenomenon. In a city where the boundary between the centre and the periphery is far from being clear-cut, newer neighbourhoods’ social fabric seems to reflect a stronger identification with the urban context. Have Romans given up on their city centre? Probably not.

“Allowing the city to coexist with tourism without losing herself in it.”

We just believe the identity of the city to be immortal. With our special kind of cynicism, we dismiss every change as temporary and insignificant, in the face of what the city has experienced in its almost 3000 years of life. But the eternal city is not eternal. On the contrary, its unique character is the result of the sometimes violent juxtaposition of different and transient identities: The authoritarian and the rebellious, the formal and the spontaneous, the new and the old, the devoted and the careless. This complexity, rather than the white marble of the Spanish Steps, is what needs to be protected − and not from an invasion by ill-behaved tourists but from the speculative, extractive and toxic relationship that tied them to the city. Perhaps the relaunch of the tourist sector that will inevitably follow the end of this pandemic can be used to set the course straight, allowing the city to coexist with tourism without losing herself in it.

_

Chiara Dorbolò is an independent architect and researcher. She studied in Rome and in Amsterdam and currently works as a contributing editor to Failed Architecture. She teaches architectural theory and practice at the Academy of Architecture in Amsterdam.

Read this Metropolis Explained and other articles in topos 111.