Metropolis Explained: New Jersey

New Jersey is called the Garden State, although its green agricultural heart is just one side of the coin. It is a poster child of suburban sprawl, too.

Billboard

Skyscrapper

Halfpage

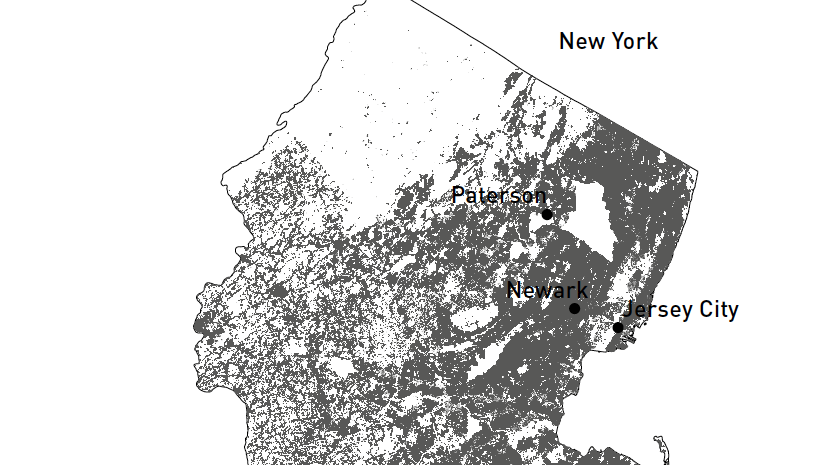

At 1.2 people per square mile, New Jersey has one of the highest population densities of the United States, comparable to the Netherlands. It is called the Garden State, although its green agricultural heart is just one side of the coin. New Jersey is a poly-centric urbanized region, too and the poster child of suburban sprawl: a continuous carpet of suburban homes, malls, office parks and distribution centers; all knit together by a dense highway network and the occasional open space.

Now, during the coronavirus crisis, many Manhattanites find the prospect of larger living spaces, a private yard and accessible public open space increasingly attractive, motivating them to consider moving across the Hudson to New Jersey, joining the ranks of the “bridge and tunnel people.” However, the Garden State still suffers a rather questionable reputation. Older folks will remember the smell of New Jersey when they crossed the large Meadowlands garbage dumps on the Turnpike, or their fear of the riots in Newark. Although the landfills are closed and Newark is back as a dynamic urban community, New Jersey is still not considered the place to go.

The face of New Jersey has changed

Most of New Jersey is a polycentric urbanized region with two core economic hubs outside the State. The North-East is a suburb of New York, the South-West is linked to Philadelphia. Only the most southern section still resembles the agricultural landscape that once defined the Garden State. Since 1857, when Llewellyn Park, America’s first planned suburb was established, the face of New Jersey has changed. Once its rural landscapes had been destinations for urban dwellers seeking a better life in a healthy environment. Government subsidies and a dense highway network further supported suburban sprawl after World War II.

New Jersey is the poster child of suburban sprawl

Today, most of New Jersey is ‘built out’ and has one of the highest population densities in the US, comparable to the Netherlands. The “corona move” further enhances existing development pressure. New high-rises emerge in Jersey City, just one subway stop away from Manhattan’s World Trade Center. “Transit Villages” with high density residential development and neo-colonial style townhouses pop up along the regional train lines providing easy commute to New York City. Today, New Jersey is the poster child of suburban sprawl, a continuous carpet of suburban homes, malls, office parks and distribution centers; all knit together by a dense highway network and the occasional open space.

The car makes New Jersey work

The car makes New Jersey work. Although people spend many hours in traffic jams, following the bike use example of Philadelphia and New York is unthinkable. New Jerseyans may ride a bike in a park but will use the car to get there. It is a challenge that the American ideology of independence and freedom, having worked well while conquering a vast continent, does not match the reality of a population density equivalent to the Netherlands.

New Jersey’s “home rule”

Washington’s Revolutionary War was also a fight for independence from British feudal landownership. High property values make it difficult to contain sprawl through planning. Farmland preservation means that the State must acquire the development rights from the farmer and preserving remaining pockets of open space in suburbia requires local governments to outright buy the land. Further, New Jersey’s “home rule” gives independence to municipalities, which hold power over land use and other governance issues. Because property tax is the main source of municipal and school funding revenues, municipalities compete for wealthy residents, further exacerbating to the ongoing building boom.

A patchwork of ethnicities

The immigration waves of the last 25 years add to the cultural diversity of the state, forming a patchwork of ethnicities: New Brunswick in central New Jersey, once the hub for Hungarian immigrants, now has a large LatinX population, neighboring Highland Park holds a thriving Orthodox Jewish community. Adjacent Edison is home to residents of Indian and Pakistani descent. Crossing from Edison into Woodbridge, Oak Tree Road is a cultural and economic hub for the south-eastern Asian community, well known even beyond the State’s borders.

Medium Rectangle

Halfpage

A patchwork of ethnicities

The immigration waves of the last 25 years add to the cultural diversity of the state, forming a patchwork of ethnicities: New Brunswick in central New Jersey, once the hub for Hungarian immigrants, now has a large LatinX population, neighboring Highland Park holds a thriving Orthodox Jewish community. Adjacent Edison is home to residents of Indian and Pakistani descent. Crossing from Edison into Woodbridge, Oak Tree Road is a cultural and economic hub for the south-eastern Asian community, well known even beyond the State’s borders.

The aftermath of racist planning through redlining

It would be an illusion to believe that all people are living happily together. Since colonial times, various groups have held animosities and were jealous of each other. When an 1878 New Jersey state law allowed the breakup of towns into small boroughs, the number of municipalities in New Jersey increased from 94 to 564. The aftermath of racist planning through redlining (withholding government-backed mortgages from African Americans) and efforts to prevent lower income residents from moving into wealthier towns with better schools still results in extreme income disparities throughout the state. But with all its challenges, New Jersey is a fascinating place that deserves a better reputation.

/

WOLFRAM HOEFER is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. He also serves as Director of the Rutgers Center for Urban Environmental Sustainability. He holds a doctoral degree from the TU München 2000 and is a licensed landscape architect in the state of North-Rhine Westphalia, Germany. He is interested in the role of urban plazas, neighborhood parks, or community gardens as places where people of diverse backgrounds can meet, interact, and possibly learn from each other.

/