The Second Bicycle Architecture Biennale launched in Amsterdam this June, featuring an array of cutting-edge bicycle infrastructural projects from around the world. But how useful are they for citizens not blessed with a bike friendly city?

The Second Bicycle Architecture Biennale launched in Amsterdam this June, featuring an array of cutting-edge bicycle infrastructural projects from around the world. But how useful are they for citizens not blessed with a bike friendly city?

Last June saw the opening of the Second Bicycle Architecture Biennale in Amsterdam, a showcase of various innovative bicycle infrastructural projects from Europe and around the world. Initiated by the BYCS foundation, and curated by NEXT Architecture, this edition was introduced at Amsterdam’s WeMakeThe.City festival, before going on tour across Europe, making stops at several major exhibitions and events, including Velo-City in Ireland, Arena Oslo, as well as events in Rome and Gent.

Bicycle Architecture Biennale: project

The biennale featured fifteen projects in total, selected for their success in extending beyond functional design solutions and tackling wider urban problems. While this allows for quite a wide berth, several themes emerge from the entries. To start with, many of the projects are defined by their relationship to pre-existing car and rail infrastructure. For instance, one involves the creative repurposing of an old highway in Auckland and another involves renovation of an old railway in Queens, New York, while a project in Barcelona has successfully overcome the impediment created by a particularly tricky section of the city’s motorway network.

Seeking synergy

In a similar vein, several projects have clearly been selected for their success in binding together previously disparate parts of the city. This goes for the Auckland and Queens projects, as well as a striking bridge in the small Dutch town of Purmerend, and another bridge in Cologne, Germany which has helped to turn its surrounding area into a new city centre.

Skyscrapper

Halfpage

Billboard

Skyscrapper

Halfpage

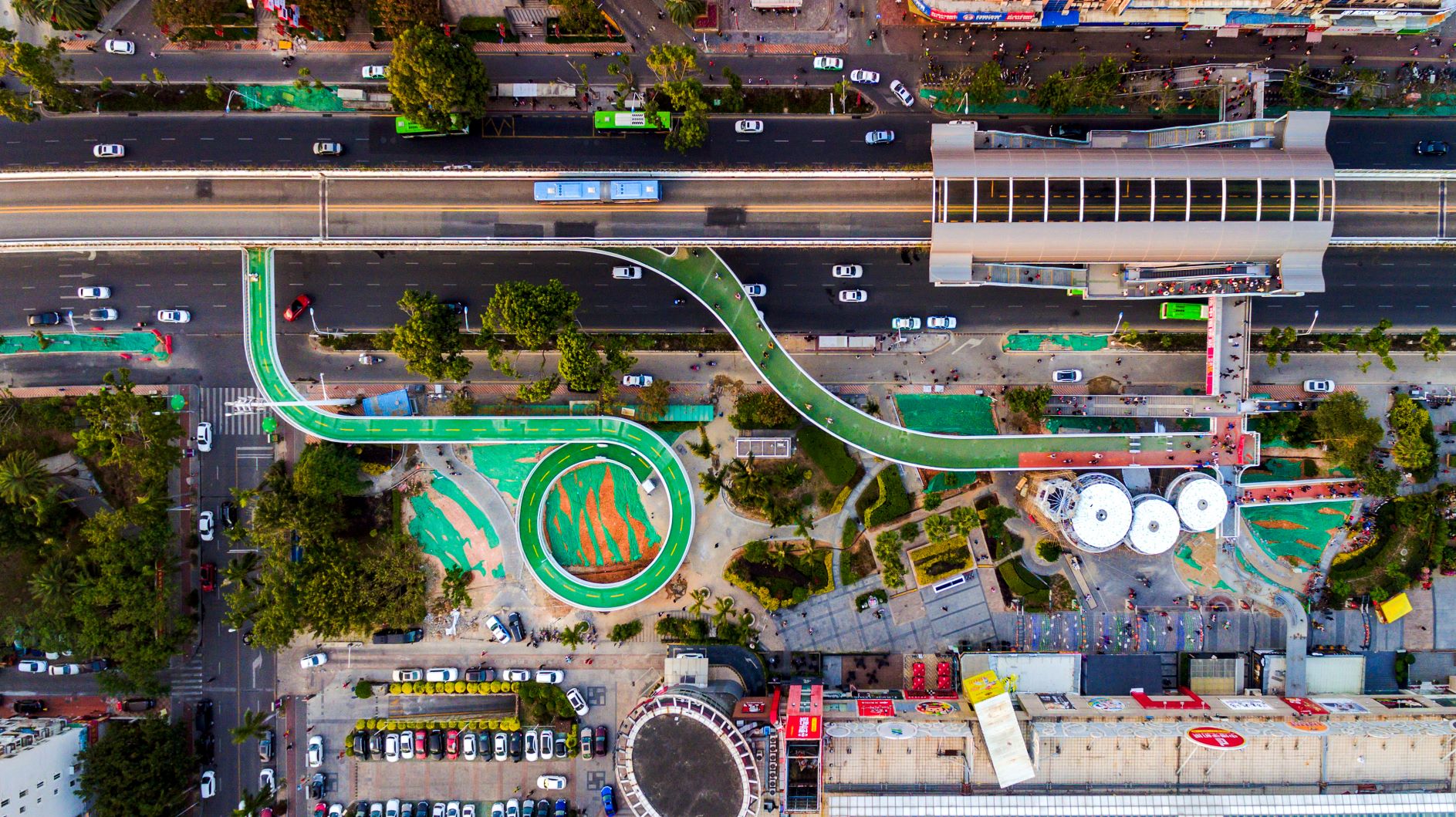

Meanwhile, there’s a very obvious focus on projects that seek to synergise with the key nodes of a city’s wider infrastructure, including a skyway that maps onto a bus rapid transit line in the Chinese city of Xiamen, a bike path that follows Berlin’s elevated U1 metro line, as well as projects in Copenhagen, Utrecht and The Hague which all adeptly insert themselves into the rapid passenger flows of these cities’ respective central train stations.

Sensitive, Stealthy, Smooth – Bicycle Architecture

If there were a golden thread observable from all these themes, it probably comes from the seeming assumption that the desired bicycle-centred city of the future is best achieved by way of solutions that are sensitive, stealthy and smoothly plugged into the pre-existing urban fabric. This is definitely an uncontroversial and sensible approach, and by no means the wrong one, but it would be great if a future edition also focused on some more bottom-up interventions. Coming as they do from Amsterdam, it cannot have escaped the founders of the Biennale that their own city’s incredibly bike-friendly atmosphere comes thanks to decades of grassroots activism from previous generations, rather than being delivered through top-down urban planning.

More grassroots, wider geography

Covering some more grassroots projects ought to also address another issue with the Biennale, that most of its successful entries are located in North and Western Europe, with four projects from The Netherlands, three from Germany, two from Belgium and one from Denmark.

Given these places are at the forefront of the move to a more bicycle-oriented urban environment, this narrow geography is to be expected. But the many cities where conditions aren’t suited to cutting edge infrastructure surely could do with some more practicable inspiration from other places that are similarly hamstrung.

To be fair to the Biennale, it’s beyond their stated scope to intervene in the various complex political situations that prevent bicycle infrastructure from being realised. But avoiding this aspect will necessarily limit its capacity for meaningful change.